By MegAnne Liebsch

July 28, 2022 — The clouds were pewter, pressing heavily into the scrub-blanketed mountains on the day I drove to the Colville Reservation in northern Washington. Unusual weather this late in spring, everyone kept telling me, but I found the effect staggeringly beautiful.

It was hailing by the time Fr. Tom Colgan, SJ, and I arrived at Sacred Heart Parish. Founded by the Jesuits in 1916, Sacred Heart is tucked into a sloping hillside in the town of Nespelem. It’s one of two Jesuit parishes I visited on the Colville Reservation — the other, St. Mary’s Parish (originally St. Mary’s Mission) in Omak, was established in 1886 by the first Jesuits to come to Colville.

Over nearly 140 years — spanning challenging and traumatic periods in reservation history — the Tribes and the Jesuits have administered these two parishes. My hope, in visiting Colville, was to understand how the relationship had persisted and changed in that time.

To be honest, though, I didn’t know what to expect as Fr. Tom steered his Prius up the gravel road leading to Sacred Heart. How do you synthesize a century-plus of complex history alongside an equally nuanced present? Can a 105mm camera lens capture all that? I had no idea.

A brief history of the Colville Reservation

Created by federal order in 1872, the Colville Reservation was designated to 12 Indigenous tribes in northern Washington: the Lakes, Colville, Okanogan, Moses-Columbia, Wenatchi, Entiat, Chelan, Methow, Nespelem, Sanpoil, Chief Joseph Band of Nez Perce and Palus Indians (today the 12 Tribes are known as the Confederated Colville Tribes). The 1.4-million-acre reservation lands occupied barely a fraction of the 39-million-acre territory these Tribes had once traversed.

Soon after, the Jesuit Fr. Etienne de Rouge arrived. Alongside Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce and Chief Moses of the Moses-Columbia, he built St. Mary’s Mission complex, which included the parish and a boarding school.

This early period of Jesuit presence on the Colville Reservation overlaps with the U.S. government’s attempt to colonize and assimilate Indigenous Peoples into white American culture — particularly through the Native boarding school policy. It is a painful and traumatizing legacy for many Indigenous Peoples, and the Jesuits are beginning to examine their role in it.

On Colville, this history is complicated, marked by both desolation and consolation. Some of the elders I spoke with celebrate Chief Joseph, Chief Moses and Fr. de Rouge, as well as the subsequent Jesuits who taught and ministered here.

What does this mean for the relationship between the Colville Tribes and the Jesuits today?

I don’t think there’s one answer to this question.

One woman told me that as a devout Catholic and a Tribal member, she’s worried for the young people on the reservation. Generations of cultural suppression — at the hands of the government and, at times, the Church — unmoors a People. She sees Native kids grasping for support, but they don’t trust the Catholic Church, and there are few elders to instruct them in traditional ways. Without spiritual guidance, the kids are lost, she told me. Still, she stressed how thankful she is for the Jesuits and the parish community; her faith is her anchor.

I’ve thought about this conversation a lot. There is a delicate nuance here that both holds the Church accountable for its previous harms and celebrates its present gifts. Everyone, whether Jesuit or Indigenous, acknowledges how the boarding school era has contributed to systemic issues on the reservation — disconnection, intergenerational trauma, substance addiction. Parishioners stressed to me, however, that the model of Jesuit ministry on Colville has changed. The Jesuits have become partners rather than teachers, working alongside Colville Tribes to address issues like poverty and to provide spiritual accompaniment.

In this way, I think St. Mary’s and Sacred Heart have become a space for grappling with past and present, for spiritual processing. And that is no ordinary feat.

Looking beyond the parish

For a miserable Saturday, Sacred Heart is hopping. Fr. Tom and I have barely unlocked the church doors when Rick — Colville Tribal member, parish musician, groundskeeper and general jack-of-all-trades — pulls up. He’s here to tinker with the sound system ahead of tomorrow’s Mass. Then, Fr. Jake Morton, SJ, and Randy, another parishioner, stop by to grab some folding tables for the Corpus Christi celebration at St. Mary’s. In the kitchen, parish administrator Nancy Montes is preparing a Father’s Day feast, replete with egg scramble casseroles, skirt steaks, sausage, donuts and smoked salmon.

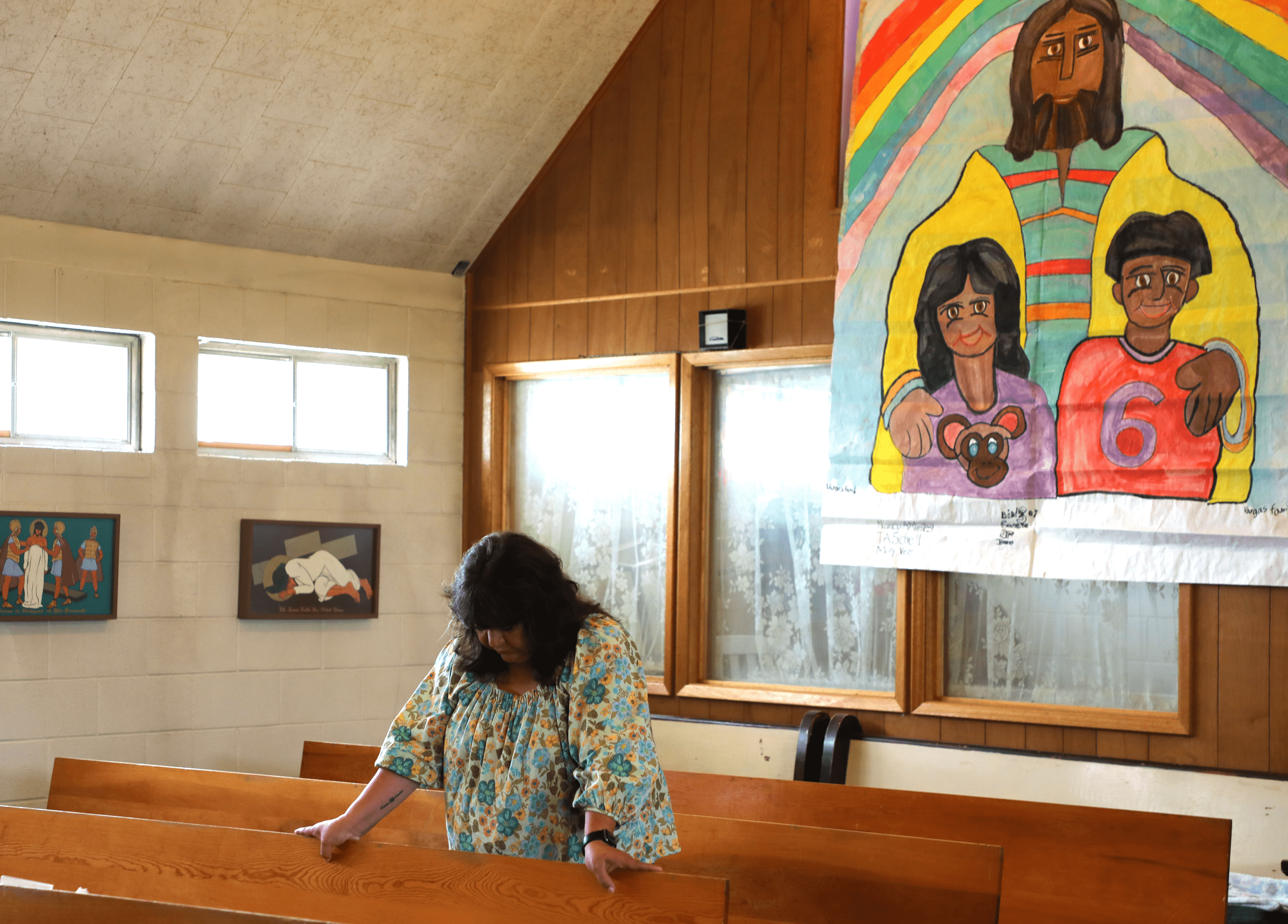

The church is essentially one room: a collapsible divider separates the pews and altar from the adjoining kitchen and dining space. Green carpets, wood paneling and Chief Joseph blankets create a welcoming warmth inside.

For those in Nespelem who don’t practice Catholicism, Sacred Heart is still a vital resource.

I spent Saturday night with Nancy Montes. Originally from Detroit, Nancy is white, but she’s lived on the reservation since 1971. She came here as a Jesuit Volunteer to teach at the school associated with St. Mary’s. She fell easily in love with the community. After marrying a fellow Volunteer, Nancy began teaching at Nespelem’s public high school, and eventually, they raised two daughters here.

Nancy is one of the engines behind Sacred Heart. Her mind holds a catalog of parishioners, elders and recently departed to pray for; her phone’s camera roll houses an archive of parish events — children posing with homemade shrines, families decked out for first Communions, a statue of the Virgin Mary sporting a Ukrainian folk scarf (“I didn’t think Fr. Jake would like that, but he didn’t say anything,” she told me with an impish smile).

We were chatting at Nancy’s kitchen table when someone frantically knocked on her front door. The hail had ushered in even more severe rains and thunderstorms, so it surprised us that anyone was venturing out on Nespelem’s waterlogged roads. A woman Nancy didn’t know explained she needed gas money, that a friend had told her to come here. Calm and stoic, Nancy called the local gas station where she and Fr. Jake have a parish tab and asked the attendant to put money on the pump for the woman.

Nancy explained to me later that, while the parish can’t give cash directly to community members, some parish funds are designated to help people pay for gas and groceries. It may seem simple, just a tank of gas on a rainy evening, but their discreet word-of-mouth network has aided people experiencing poverty, domestic violence and other emergencies on this remote reservation.

Honoring traditions

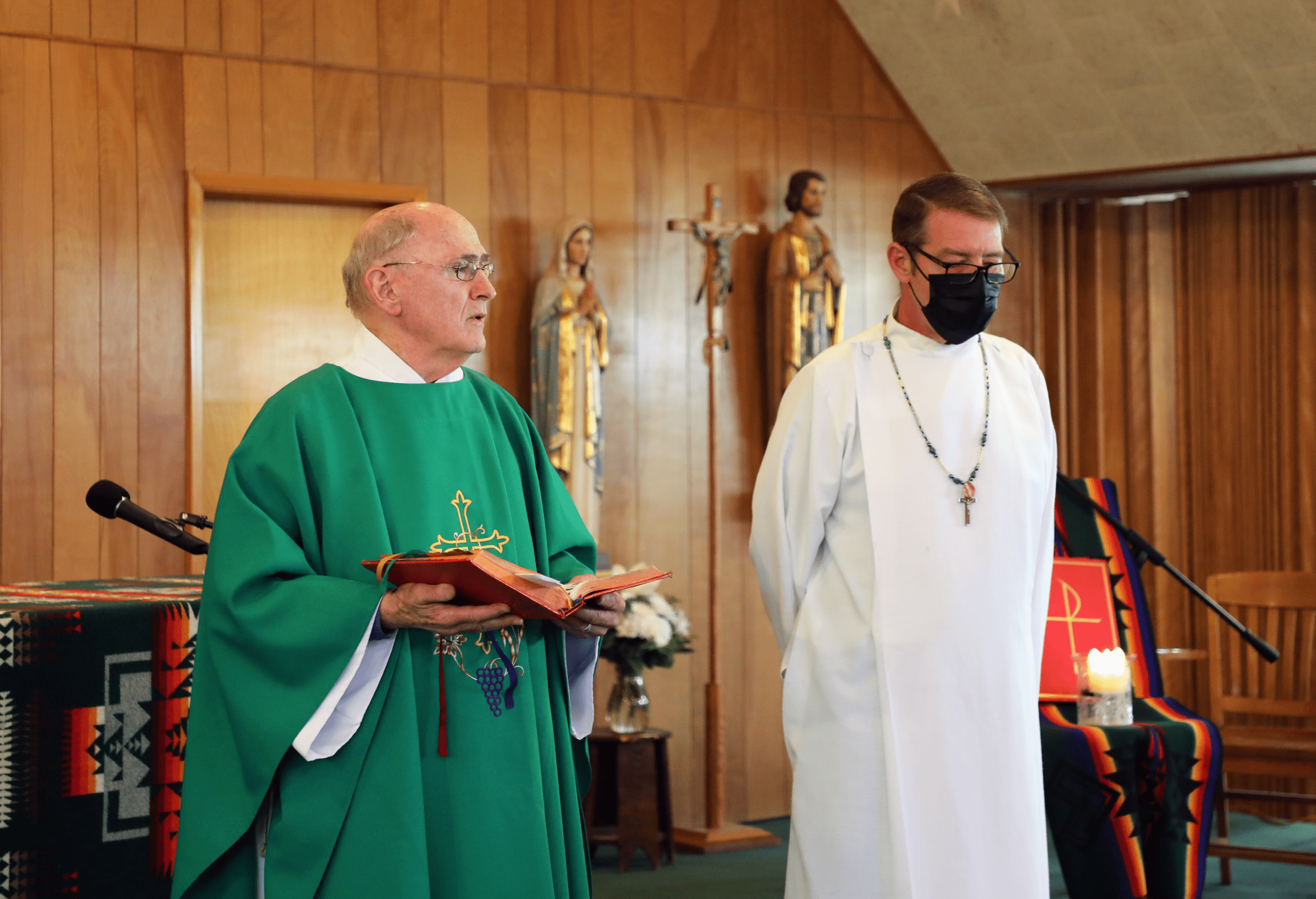

Mass at Sacred Heart is scheduled to start at 8 a.m. on Sunday morning, but this is more of a suggestion. By the time everyone files in and the procession starts, it’s more like 8:20. No one seems to mind.

Growing up Catholic, I often heard some variation of the platitude: “You can go to a Catholic Mass anywhere in the world, in any language, and you’ll be able to follow it.” But now I find this to be an oversimplification — a disservice, really — of the adaptability of the Catholic rite.

At Sacred Heart, Mass is suffused with Native ceremony and music. Before the Eucharist is consecrated, a parishioner (typically an elder) smudges the host and the altar with a smoking bundle of sage. Smudging is an Indigenous practice in which plants such as sage and cedar are burned, creating a smoke to cleanse the spirit. After cleansing the altar, the elder traverses the pews wafting smoke over each parishioner. At the end, the parish sings a hymn in a Salish dialect.

Sure, the scaffolding of Mass remains the same. But its content and symbols respond directly to Nespelem’s context. This synthesis of tradition is important, especially as the nature of the Jesuits’ presence on Colville has changed.

In the past, there were multiple Jesuits living on Colville full-time. Now, only Fr. Jake lives there, while Fr. Tom commutes between Nespelem and Spokane. Because Fr. Tom is only present on the weekends (though he joins parish events via Zoom during the week), people like Rad — Deacon Radford George — and Nancy helm day-to-day parish operations. While there are challenges to this approach, I think it opens a space for lay leadership. It recalibrates the relationship between Jesuits and the Tribes, making ministry on Colville a joint project.

Corpus Christi

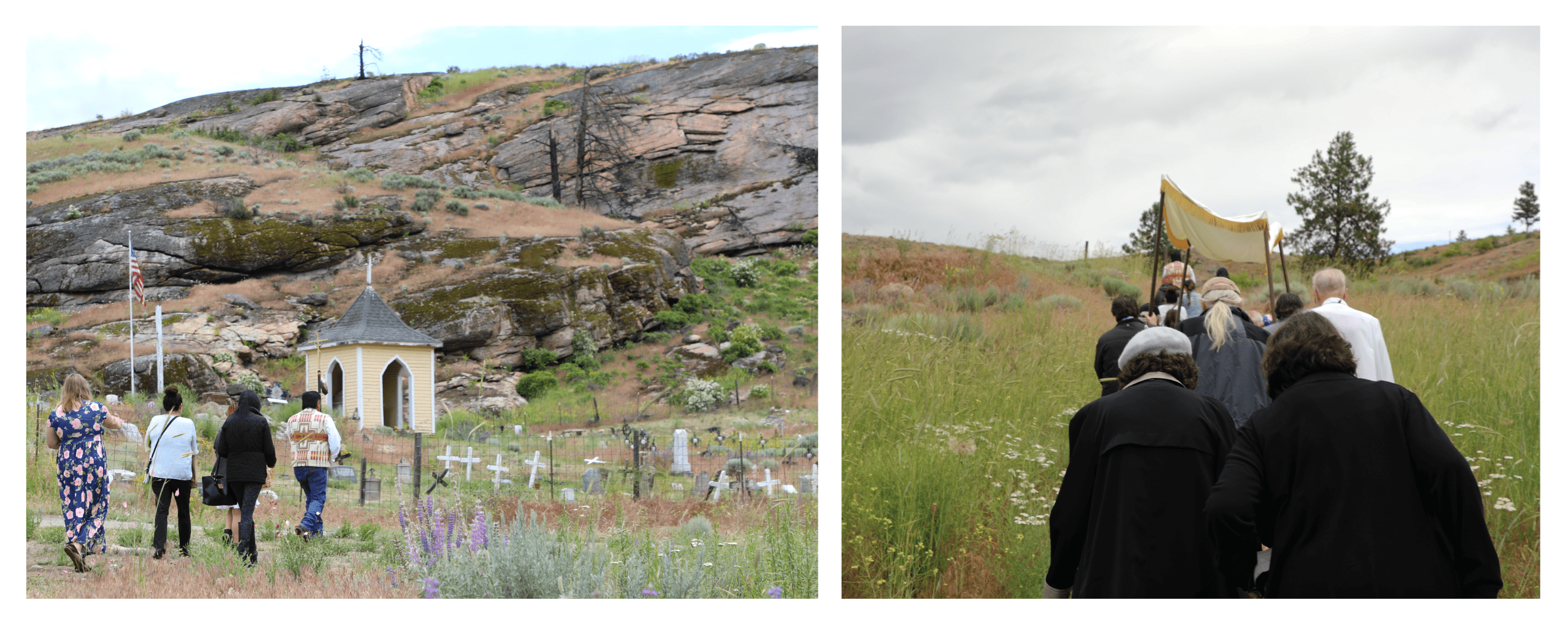

By noon on Sunday, the rains had eased into fog, just in time for the Corpus Christi procession at St. Mary’s in Omak. The Feast of Corpus Christi celebrates the holiness of the Eucharist. Traditionally after Corpus Christi Mass, the Eucharist (ensconced in the monstrance) is paraded throughout the community, stopping for prayer at various stations, which are bedecked in flowers and wreathes. It’s a joyful day. In the Colville parishes, families make stations that resemble teepees or longhouses, draping small wooden frames with colorful scarves, images and flowers.

The tradition dates back to the first Jesuit on the reservation, Fr. de Rouge, who brought the Corpus Christi procession to Colville from his native France.

After Mass, a group of parishioners trek through the wet grass, each with a processional task. At the head, an usher carries a crucifix decorated in the four medicine colors and an eagle feather. He’s followed by a family of women who sprinkle a carpet of rose petals before the Eucharist, which is carried by Fr. Jake under a canopy hoisted by four men. After the canopy follow the elders, and then me, my feet catching clumsily on rocks because I’ve got my eyes trained on the camera viewfinder.

Fr. Jake carries the monstrance under a canopy (left). Three Colville women carry baskets of flower petals to spread before the Host in procession.

Fr. Jake carries the monstrance under a canopy (left). Three Colville women carry baskets of flower petals to spread before the Host in procession.At the first stop, the community cemetery, a Colville Tribes elder leads us in a prayer to the four directions, which correspond to colored segments of the Salish medicine wheel. North, for example, represents elders and ancestors. As the elder directed us to turn to the north, he spoke of the ancestors at rest here. My throat tightened. I found something so profound, so promising in this traditional prayer, said on a Catholic feast day in a Catholic reservation cemetery. To me, this prayer embodied the changes in Jesuit-Native ministry. There was no ultimatum, no compulsion to choose Native or Catholic, medicine wheel or rosary.

MegAnne Liebsch is the communications manager for the Office of Justice and Ecology of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. She holds an MA in Media and International Conflict from University College Dublin and is an alumna of La Salle University. She is based in Washington, DC.