By MegAnne Liebsch

November 15, 2022 — When Santos listens to Cyndi Lauper’s hit power ballad “Time After Time,” he hears the chorus as a love letter from God. He explains his thinking simply: “If you’re lost, you can look for God.”

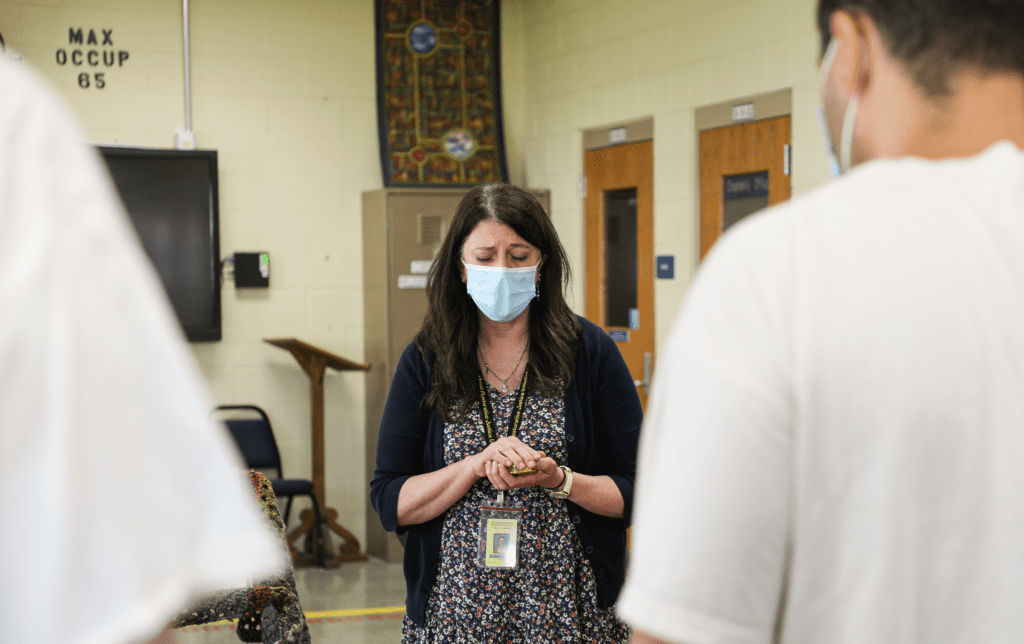

“Cyndi Lauper wrote it as a love song, but we use it in here as a God song,” adds Jennifer Kelly, who is seated next to Santos. We’re gathered in a sterile, white and grey room, which Jennifer has spruced up with a flowery tablecloth, electronic candles and icons of the Sacred Heart. “Here” is the Mental Health Unit of the Monroe Correctional Complex (MCC) — a prison about 30 minutes northeast of Seattle.

Santos is incarcerated at MCC. He met Jennifer a few years ago, at one of the Ignatian retreats that she runs in Washington state prisons. The retreats are part of a program called the Jesuit Restorative Justice Initiative Northwest (JRJI NW), which offers spiritual support, guided retreats and other prayer services designed specifically for incarcerated individuals.

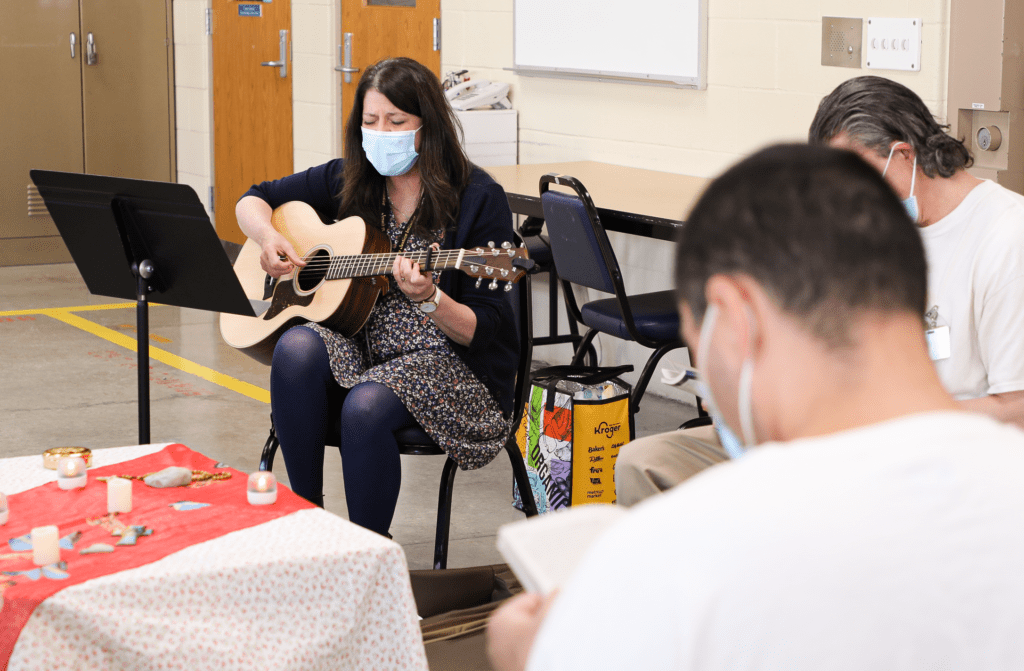

For Santos, Jennifer’s singing is the best part of JRJI NW’s programs. An accomplished musician with a glassy smooth voice, Jennifer has found that music is a powerful bridge, connecting her and the people attending her retreats.

Cyndi Lauper’s verse may be an unlikely spiritual vehicle, but the song carries a weighty power for Jennifer and Santos. “I think, Santos, the reason you and I know [this song] so deeply is because prison is full of the one God wants to find,” Jennifer tells him.

Then, eyes closed, head and chin notched upward, Jennifer sings.

If you’re lost you can look and you will find me

Time after time.

If you fall, I will catch you, I’ll be waiting

Time after time.

I can see it in his smile, in the way he hums along — how this song transports Santos into a space beyond these impenetrable walls. It’s more than escape, though. Cached in this song’s lofty notes is a mutual understanding between Jennifer and Santos. A musical nod that says, I too have lost and been lost. I have wanted desperately to be found.

More than prisoners

Fittingly, JRJI NW was born out of a concert. In 2015, Jennifer’s band played what was meant to be a one-time concert at Monroe Correctional Complex. During set-up, Jennifer got to chatting with three incarcerated men — Bill, Mark and Dylan — helping to set up amplifiers and microphones. She mentioned her previous experience with Ignatian retreats. Suddenly, Bill lit up: “An Ignatian retreat? I’ve been praying for one for years!”

Jennifer knew she had to do something. She reached out to Fr. Mike Kennedy, SJ, who founded the Jesuit Restorative Justice Initiative (JRJI) in California, and he invited her to shadow his work in California prisons.

True to its name, JRJI follows a framework of restorative justice that sees crime as a fundamental violation of human relationships. While the U.S. criminal justice system largely emphasizes punishment, restorative justice seeks healing for offenders, victims and the communities impacted by crime. Fr. Kennedy believes that spiritual and retreats are a key resource in this healing. Through a raft of spiritual and educational programming, JRJI creates spaces where incarcerated people can “place themselves in the presence of a loving God who sees them for who they are – not mistakes, but rather individuals in need of healing.”

The criminal justice system follows a causal if-then logic that determines quantifiable factors like sentencing and re-entry outcomes. Prison programs often focus on these measures — job and skills training, continuing education — all of which are crucial to transformation. But restorative justice is also concerned with rebuilding relationships. That kind of healing is largely unquantifiable.

“We don’t heal in our intellect,” Jennifer explains. “We heal in our memory, our hearts and our feelings.” While Jennifer acknowledges healing is ultimately self-led, JRJI provides spiritual tools, such as memory meditation and Ignatian conversation models, to help people in that process.

When Jennifer arrived in Los Angeles to shadow Fr. Mike, over 3,000 people were participating in JRJI California programs, but the model hadn’t expanded beyond the state. After a year of learning, Jennifer returned to Seattle, eager to bring Ignatian retreats to the men she met at MCC.

Over 28 men attended the first retreat, many of whom weren’t Catholic or even Christian. Convening interfaith spaces is no small task in prison, where religious affiliation is often divisive. Dylan, for example, is Protestant, and he didn’t know much about Ignatian spirituality but the idea of a full-day retreat intrigued him. Most of MCC’s weekly religious services are an hour long. To have a full day of prayer, community and live music felt luxurious.

“We thought it was a great thing to do,” Dylan tells me. “A day to sit and meditate, to be with the brethren, be with some of our sisters, for outside partners to get to know us, not just as prisoners but as part of the Body of Christ — that was an important detail.”

From 28 initial retreatants, the program quickly snowballed, and subsequent retreats capped out at 60 attendees. The retreats created safe environments, where people are not confined by labels like inmate or chaplain. “What the Ignatian retreats did was allot us that time in a secure fashion to be vulnerable with each other,” says Dylan. Prison prioritizes the immediate, often out of self-protection. Dylan says he rarely thought about others, he didn’t even process what he was feeling most days.

“We’re thinking about, ‘What’s for dinner today? Can I grab that table for card games today?’” Dylan explains. “We’re not given a lot of opportunities to say, ‘How did this make you feel?’”

Ignatian meditation probes deeper. Those early retreats pushed Dylan to look inside himself in a way he never had before and then to share those reflections with others. The community became crucial to Dylan, and in the last six years, he hasn’t missed a single retreat.

As JRJI NW’s founding director, Jennifer is now overseeing a rapidly expanding ministry. This summer, the organization hired its second ever full-time employee, Fr. Joe Kramer, SJ. Together, the pair will lead retreats and Ignatian programming in four prisons and one jail across Washington.

“I love this work so much and I can’t believe I got called to it,” Jennifer says. Heart on her sleeve, she begins to cry when I ask her what JRJI NW means to her.

“People tell me how our style of programming has brought them healing and personal growth, changed their lives,” she explains. “That is humbling and moving and stunning, and exactly what I would have hoped to give my life to when I first got my theology degree decades ago.”

Discernment and transformation

In the toolbox of Ignatian spirituality, “discernment of spirits” is the hammer—fundamental and used constantly. If you don’t know how to use a hammer, you’re not going to build much, likewise with discernment and Ignatian spirituality. Ignatian discernment calls us to explore our deepest emotions, our motivations and desires. But people who are locked up rarely have the privilege to examine let alone express their feelings.

“I come from a long line of truckers. You didn’t cry. Men don’t cry. You suck it up, rub some dirt on it, get back out there,” Justin Countryman says with a hearty laugh. “Within the prison system, that’s just culturally around you. You don’t show emotion, you don’t show weakness.”

Often called “Country” by fellow inmates, Justin’s name seems to match his personage, from his thick wiry beard to his family background and his rough-and-tumble attitude. One might guess (albeit incorrectly) that Justin subscribes to the hyper-masculine credo he grew up hearing. But Justin is warm and thoughtful. He told me he was drawn to JRJI NW by the welcoming spirit of Jennifer and other retreatants. On his own, he rarely meditates, but Justin loves Jennifer’s guided meditations, which always end with journaling and sharing time.

“There are times when people are sharing and hardly anyone is able to get through it without tearing up,” Justin says. “That’s really hard to do in a place like this, showing vulnerability, showing emotions is a no-no. You don’t want to show weakness. So being able to sit in a group like that and not feel like you have to hold that back is a pretty amazing feeling in a place like this.”

Sharing didn’t always come easy, though. Jennifer remembers the first few programs that Justin attended. She describes him as a swimmer, slowly walking into a cold ocean, acclimatizing before diving in. “I love that about you,” she tells him. “There’s an intentionality and an integrity about how you move.”

Over the last year, Justin says JRJI has helped him process and express himself “on all levels rather than who I’ve been taught to portray.” This alignment results from a discernment of spirits—a process in which Justin peeled back the layers of who he was told to be until he found who was underneath, who God wants him to be. That knowledge has been transformative.

According to the Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 33 percent of people released from Washington prisons will be locked up again within 3 years. Once released, people face a barrage of challenges from finding affordable and safe housing to getting a job and reconnecting with loved ones. For Justin, there’s also a problem of perception: People who do time are seen as less than human, hardened and devoid of empathy. That’s why so many people are drawn to JRJI’s programs.

“It’s a way to help people start to grow and change and evolve,” says Justin. “So that when we get back into society we can feel empathy, we can feel and have emotions, and we can show people that, so that we’re seen more as humans again rather than felons.”

A labor of love

“Are you the Catholic ladies?” A man shouts from across the yard. Along with MCC’s Catholic chaplain Gloria Kempton, Jennifer and I are leaving our last unit visit at MCC. Dusk is falling around us in rosy pinks and lavenders.

The man introduces himself and explains, “I’ve heard what you do for the men, and I wanted to thank you.” Within five minutes of chatting, Jennifer is promising to bring him a rosary next week and inviting him to JRJI NW’s services.

Clearly, Jennifer’s reputation precedes her. Over the course of the day, I met dozens of JRJI NW participants, and nearly all of them spoke of their deep admiration of Jennifer. I suspect her warm sincerity is among the main factors that draw people to JRJI NW programs.

Jennifer has a buoyant energy, and it surges through the people around her, too. People light up instantly when they encounter her, even if just for a passing moment in the corridor. But she’s also thoughtful, asking probing questions or recalling the details of people’s struggles from many years past.

“Her faith drives the fruit of the Spirit to bloom in the hearts of people of all faith traditions,” says Kenneth, who hasn’t missed an Ignatian retreat in six years. “She makes her considerable effort seem effortless, but knowing my sister in Christ, it’s simply a labor of love she engages in without a second thought. Her heart is in the right place, without agenda or motive.”

Kenneth has been incarcerated — or “in monastic time-out” as he puts it — for 14 years. He says Jennifer pours her heart into her work, and he knows it weighs on her too. She worries for her most vulnerable participants, such as those with serious mental health struggles.

I think it’s this balance of care and concern, of grief and joy that makes JRJI NW so special. Not only does Jennifer care deeply about each retreatant, she creates spaces that encourage others to care, too. “This is what has drawn me to her as a kindred spirit in service,” Kenneth says.

‘Who God wants to find’

When Jennifer finishes singing “Time After Time” for Santos, she says simply, “It’s true. I feel when I sing it that God’s singing to you, Santos.”

As if caught off guard by memory, she launches into a story. Years ago, when Jennifer was battling breast cancer, she was afraid she might die and leave behind her 12-year-old son. Desperate that he know how much she loved him, Jennifer told him dozens of times a day: I love you, I love you, I love you.

“The first time he said, ‘I know,’ instead of, ‘I love you, too,’ made me really happy,” Jennifer says. Turning to Santos, she continues, “The fact that you take it in and that you know God loves you. I just think it makes God really happy.”

Santos is silent for a few seconds, choked with emotion. “That’s nice,” he finally replies. “That’s a good feeling.”

I don’t think many people have told Santos that God finds joy in him. I remember what Jennifer said earlier, that prison is full of people who God wants to find and that God delights in finding them. It’s a radical notion. Whether inside or outside of prison, we all wander, lost in the wilderness of our mistakes. And we all crave love and forgiveness — most of us just don’t know how to ask for it. Or we’re too proud to admit it.

JRJI is concerned with the people who do ask for help, who are looking to find themselves and God. Many incarcerated people feel themselves defined by the worst moments of their lives, moments that they are trying to reconcile or heal daily. But to Jennifer, they are not reduced to a crime or a sentence. Jennifer sees them through God’s eyes — as sources of joy.

§

JRJI NW is a work of Jesuits West Province that is working to become an independent organization. Stay up to date through JRJI NW’s email listing.

If you’d like to support their work, click here. Please designate any donations to “Jesuit Restorative Justice Initiative Northwest.” Alternatively, you can mail a check to 1211 East Denny Way #105 Seattle, WA 9811. Questions? Email infojrjinw@jesuits.org.

MegAnne Liebsch is the communications manager for the Office of Justice and Ecology at the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. She holds a master’s in media and international conflict from University College Dublin and is an alumna of La Salle University. She lives in Washington, DC.