By William Bole

November 13, 2014 — It was one of the most glaring and brazen human-rights crimes of the late 20th century.

In the predawn hours of November 16, 1989, an elite battalion of El Salvador’s military forced its way into the Jesuit residence at the University of Central America, or UCA. The university, led by its president, Father Ignacio Ellacuría, SJ, had become a stronghold of opposition to human rights abuses committed by the U.S.-backed military.

On that night, soldiers dragged five priests out of their beds and into a courtyard, made them lay facedown on the grass, and fired bullets into their heads. They went back inside and killed another Jesuit. Then, searching the residence further, they found a housekeeper and her teenage daughter crouching in the corner of a bedroom, holding each other. The gunmen shot them too.

Twenty-five years later, many are still waiting for justice in the case of the murdered Jesuits and women. None of the top military commanders who issued the orders to kill was ever prosecuted for the crimes. There is now, however, renewed interest in bringing them to trial. Ramping up the pressure are global human rights groups and Spain, which claims jurisdiction in the case because five of the six Jesuit victims were Spaniards.

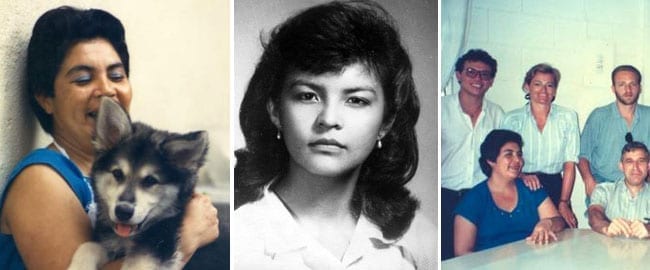

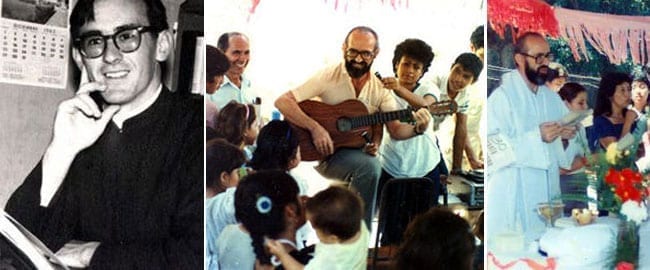

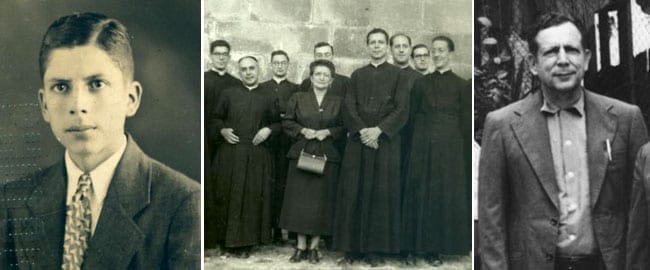

Amid these stirrings, the Society of Jesus is seeking something larger than legal justice. Many members of the order are promoting the legacies of those who perished in the Jesuit massacre — the Fathers Ellacuría, Ignacio Martín-Baró, Segundo Montes, Amando López, Joaquin López y López, and Juan Ramón Moreno, as well as Julia Elba Ramos and her daughter, Celina Maricet Ramos. The eight are often referred to simply as “the martyrs.”

Julia Elba Ramos (left and right) and her daughter, Celina Maricet Ramos (center)

U.S. Jesuits say they are striving for the kind of justice that brings out the truth, forges reconciliation and looks ultimately to the future. “It’s not about vengeance or punishment, but about letting all of the truth be known,” said Father Stephen A. Privett, SJ, former president of the University of San Francisco, a Jesuit institution.

A Road to Reconciliation

Much of the truth about the murders at the UCA is already known. In the aftermath of the atrocity, a U.S. Congressional investigation and a United Nations-sponsored truth commission helped establish the facts of the case, including the orders given by higher-ups. Fr. Privett, who knew the UCA Jesuits as a refugee worker in El Salvador, in the late 1980s, says he would like to see this truth “recognized by a judicial process” in that country or internationally.

But the Jesuit is speaking also of a larger truth — the 12-year civil war in El Salvador and social wounds that have never healed. The war ended in 1992, after Congress voted to throttle back military aid to the right-of-center Salvadoran government, mainly in response to the Jesuit killings.

“This case has become the lens through which you look at the whole period,” Fr. Privett said, stressing that more than 70,000 civilians lost their lives, primarily at the hands of the Salvadoran military and paramilitary death squads. “It allows us to see the truth of those years. It validates the stories and experiences of the victims.”

That, he believes, is a difficult though necessary road to the long-delayed social healing and reconciliation in El Salvador.

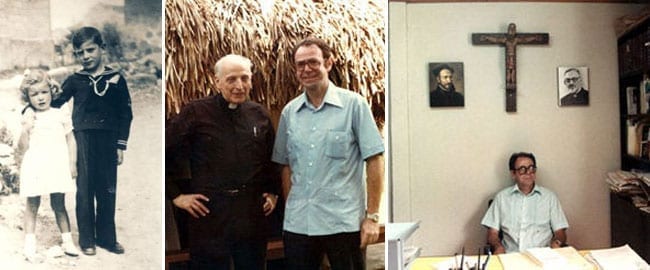

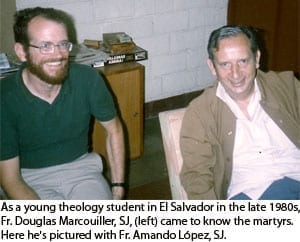

Father Douglas Marcouiller, SJ, who stepped down this past summer after five years as provincial or leader of the Missouri Province of Jesuits, agrees. “It’s hard to go forward without acknowledging the truth of that history,” said Fr. Marcouiller, who was close to the six priests and two women as a newly ordained Jesuit doing advanced theology studies at the UCA, in 1986 and 1987.

Still, during an interview he steered the conversation away from the killings and the case, and toward the eight who were his friends.

“It’s the witness of their lives that matters,” he said. “The case is important. But the focus shouldn’t be primarily on the people who pulled the trigger, or the ones who gave the orders. It should be on the martyrs and their commitment to the Gospel, the kind that leads us to defend the lives of the poor today, going forward.”

The UCA has remained at the leading edge of social research and action in El Salvador. The concerns today range from economic inequality and environmental issues such as water rights to immigration and the plight of unaccompanied minors fleeing the country. Jesuits in the United States have stayed involved as well. For example, Fr. Marcouiller, a trained economist, spends part of every year teaching a course in economics at the university. He will soon begin serving in Rome at the Jesuit Curia, international headquarters of the Society of Jesus.

Father Thomas H. Smolich, SJ, who has spent the past eight years as president of the U.S. Jesuit Conference, based in Washington, draws a link between the Jesuit martyrs and those current issues.

“If they were talking to us now, they would say, ‘Don’t lionize us. Use what we did to take up the challenges today,’ ” said Fr. Smolich, who is assuming a new role as international director of the Jesuit Refugee Service. “What is Christ calling us to do at this point? What does it mean to be in solidarity with the poor, in 2014?”

The Martyrdom Factor

And yet, the UCA Jesuits and their two lay collaborators are remembered for what many see as their martyrdom.

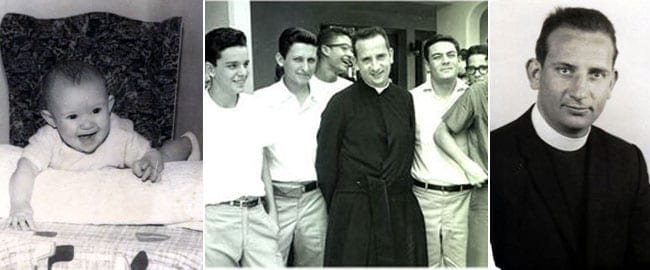

Father Ignacio Martín-Baró, SJ

The most widely revered among them is Fr. Ellacuría, a Spanish-born theologian who had emerged as one of the country’s most prominent voices on behalf of peace and the poor. The planning for the massacre began with an order to assassinate Fr. Ellacuría “and leave no witnesses,” according to the U.N. commission’s 1993 report. As it turned out, there was at least one daring witness — Lucía Cerna, a housekeeper who happened to spend the night with her family next door at the old, unoccupied Jesuit residence. She publicly identified the killers, by their uniforms, as government soldiers, at a moment when the government was diverting blame to left-wing rebels. Then she and her family were whisked out the country with the help of Jesuit leaders.

Each of the priests, not just Fr. Ellacuría, had been carrying out what Jesuits like to call “the faith that does justice.”

Fr. Martín-Baró, social psychologist and philosopher, was director of the University Institute of Public Opinion, the only group in El Salvador that polled among the poor for their opinions. Fr. Montes led the Human Rights Institute at the university. Fr. López, philosopher and theologian, was pastor of a poor church on the periphery of San Salvador. Fr. López y López directed Fe y Alegria (Faith and Joy), a vocational training program for impoverished youth. Fr. Moreno was serving at the Center for Theological Reflection, which addressed questions of faith and justice.

Cerna, who now lives in California, says of the six Jesuits, “They empowered me with faith… They had respect for me, and they taught me self-respect.” She recalls them and the 1989 rampage in a new book, “La Verdad: A Witness to the Salvadoran Martyrs“ (Orbis Books/Santa Clara University), written with historian Mary Jo Ignoffo. Fr. Marcouiller said he too learned life lessons not only from the Jesuits but also from the housekeeper and cook, Julia Elba Ramos, whom he recalls as a strong and passionate woman who often “danced around the kitchen to the oldies channel.” She had “the gift of hopefulness,” he said.

The victims were not killed necessarily because they were Christians, but they are martyrs nonetheless, in the view of many.

“When you sacrifice your life because of your active support for the marginalized, you are a martyr in the traditional sense. You are witnessing to a transcendental reality that is not comprehended by others, particularly the folks who are wielding the power,” explained Fr. Privett, underscoring that work for justice is an inherent part of Christian faith.

For him and many others, the truth of what happened on November 16, 1989, is ultimately bound up with this truth of martyrdom.

“I think the Church needs martyrs in every era, to remind us that we can never be comfortable with the world as it is. We have to work for a better world, and often we pay a pretty heavy price, but that price is not that heavy when you look at it through the lens of the Resurrection, or through the eyes of the martyrs,” Fr. Privett added. “It’s a really important part and a dynamic piece of our tradition that keeps us moving and engaged, never comfortable with any status quo this side of heaven.”

Father Joaquin López y López, SJ

Fr. Smolich related a Catholic saying — “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” As evidence, he points to Jesuit universities in the United States, where many students have been drawn to faith-and-justice causes after learning about the Salvadoran martyrs. The ones who are in college today were not yet born in 1989.

For this and other reasons, Fr. Marcouiller says he is not really mournful on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the killings. What he feels at this turn, he said, is “gratitude for what God was able to do through them, and in their lives, for the people of El Salvador.”

William Bole is a contributing writer whose work has appeared in publications ranging from the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times to Commonweal and America, among others. Much of his writing explores religion, ethics, politics and intellectual life.

Images of the martyrs via www.uca.edu.sv. Photo of Fr. William Rewak, SJ, and Fr. Ignacio Ellacuría, SJ, courtesy of the Santa Clara Archives & Special Collections.

Do you want to learn more about vocations to the Society of Jesus? Visit www.jesuitvocations.org for more information.