What We Have Learned

St. Joseph College, Bardstown, Kentucky

Image taken by Kenneth C. Zirkel

St. Joseph College was established in 1819 under the auspices of Benedict Joseph Flaget, the first bishop of Bardstown and one of Kentucky’s largest slaveholders. The college relied on enslaved labor over the course of its history. By 1840, when future bishop of Louisville Martin John Spalding was president of St. Joseph, the college held 18 people between infancy and 54 years of age in slavery, and likely relied on many others who were loaned or rented to the college.

The Society of Jesus took over administration of St. Joseph College and St. Joseph Cathedral from the diocese in 1848. On July 24, 1848, when Walter Hill, SJ, and Jesuit scholastic Frederick Garesche began their journey from Missouri to St. Joseph College in Bardstown, and St. Xavier College in Cincinnati, respectively, an enslaved man drove them and their luggage by wagon on the first leg of the journey. Upon their arrival at St. Joseph College, the Jesuits decided to keep all the enslaved people currently at the college, except Charles, Dave, his wife, Maria, and their children, who left over the course of the month of August 1848. It appears that Dave, Maria and their family became free, and that Charles, still enslaved, was sent to labor elsewhere; researchers are still working to confirm these details. From 1849 to 1865, between about 10 and 20 enslaved people labored for the Jesuits at Bardstown. Researchers are working to determine their names and more about their lives.

Enslaved people worked alongside students and Jesuit brothers, preparing the college through whitewashing the walls and working in the kitchen. They constructed new buildings and a stable, and worked on the upkeep of existing buildings. At one point, the cabins where enslaved people lived burnt down. While no one was hurt, they may have lost whatever possessions they had, and they had to rebuild their quarters.

Note: Enslaved people who were rented from their owner to another person were often described as “hired” or “hired out.” This does not mean they were being paid. Slaveowners lent or “hired out” enslaved people to other owners, and the slaveholders received the pay, though they sometimes allowed enslaved people to have a small cut of that pay to incentivize them be obedient and keep working.

Jesuits at St. Joseph College relied extensively on enslaved labor rented from other local slaveowners, including priests, women’s religious orders, and Catholic colleges and seminaries. Some of the people they rented, including Magdelin, Agnes and Tom, and Sam, were owned by Bishop Benedict Joseph Flaget, Bishop Martin John Spalding, and Reverend James Madison Lancaster. Jesuits at St. Joseph College hired Eliza from Reverend J. B. Hutchins, president of St. Mary’s College in Kentucky. They rented Edward from Reverend Francis Chambige, president of St. Thomas Seminary. And they sent an enslaved man, George, to Nazareth, Kentucky to serve the Sisters of Charity. In 1850, Jesuits transferred their own enslaved woman, Mary, from their novitiate in Florissant, Missouri, to the college in Bardstown, Kentucky.

Jesuits asked the Sisters of Loretto to aid in running the college by maintaining the students’ dining room, dormitories, and infirmary from 1848 to 1851. The Loretto sisters relied on enslaved men and women to perform the “heavy drudgery” of this work. Sister Theresa took over management of the kitchen and the enslaved people who labored within it. Michael Nash, SJ, recalling his time at St. Joseph College in the 1840s, noted, “The servants of the house were negroes, but under the supervision of matronly ladies.” Fr. John Baptist Duerinck wrote in September 1848 that “the black boys sweep the house and mind the boys’ refectory.” He also commented that sometimes the college’s pigs would escape into the college yard outside of President Peter Verhaegen’s window. “The old gentleman used to grumble and scold when he would see the pigs in the yard,” and would call upon an enslaved boy to drive them away, Duerinck wrote.

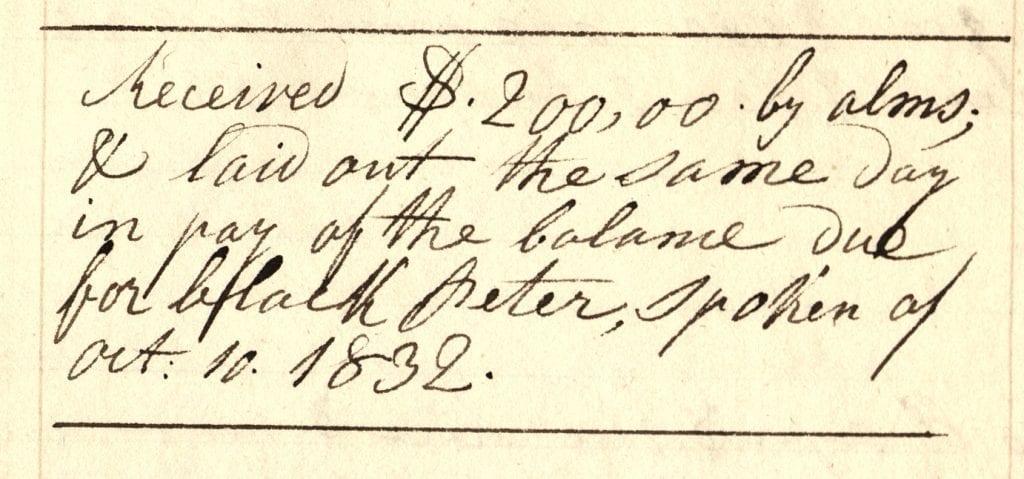

In 1849, Jesuits forcibly relocated a man named Peter from their seminary in Missouri to St. Joseph College in Kentucky, separating him from family as a punishment.

Jesuits at St. Joseph College accepted enslaved people from the parents of students in payment of tuition. Matilda, who was enslaved to Basil R. Clark, labored at St. Joseph College as a form of tuition payment for his son Francis Clark. An unpaid balance in the account of D. Slaughter, a parent, was marked in the college ledgers as to be “taken in negro hire, or lost.” While white students received an education made possible by the labor of enslaved people, students of African descent were dismissed from the college for having been proven to be “of mixed blood.” We are researching their stories and will share them in the future.

Union and Confederate forces occupied St. Joseph College and Church three different times during the Civil War, causing students to flee to their homes. The priests turned their attention to ministering to wounded soldiers convalescing in the college, and increased their ministry efforts toward people of color by devoting more time to catechism classes and holding masses for African Americans in the community. Due to financial difficulties, most Jesuits left St. Joseph College in 1868 and focused their attention on other colleges and churches in the Missouri Province.

Eliza Frances Smith and Robert Rudd were enslaved sextons in St. Joseph Church, as were some of their children. One of these children was Daniel Arthur Rudd, the founder of the American Catholic Tribune and what is now the National Black Catholic Congress.

As at other Jesuit sites near the end of the Civil War, Jesuits spent more time ministering to free and enslaved people of color in increasingly segregated spaces. Jesuit Father Charles Truyens began holding catechism classes for people of color before evening prayers on Sundays. Increasingly, African Americans attended religious services on the second Sunday of every month, and some weekly. Eventually, Truyens established a church for people of color in Bardstown, and purchased a lot from Mrs. Margaret Hagan in order to establish St. Monica’s Colored School. It appears, however, that Truyens, who died in 1867, was not able to see the school to fruition. Father C. J. O’Connell, who took over operation of the school in about 1878, said that the one-room schoolhouse “has been conducted on this property since 1872.” O’Connell began expanding the building so that the school grew from a few pupils to a hundred children.

Though part of the original college still stands, St. Joseph College is no longer in operation. Research on the enslaved people who belonged or were hired out to the Jesuits in Kentucky is ongoing. We do not yet know much about what their lives were like, and we are still working to trace the genealogy of their descendants. We will continue to update this page as we learn more.

This research was compiled by Kelly L. Schmidt.

Recommended citation: Kelly L. Schmidt, “Enslavement at St. Joseph College, Bardstown, Kentucky,” Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project, 2020.

Updated: March 2020

4511 W. Pine Blvd.

St. Louis, MO 63108

SHMR@jesuits.org

314.758.7159